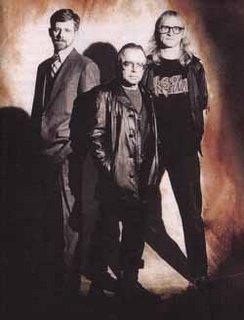

There is a Taoist myth of the Three Celestial Ones, the Celestial Worthy of Primordial Being, the Celestial Worthy of Numinous Treasure and the Celestial Worthy of the Way and Its Power, three male deities who are said to live beyond the Big Dipper. They descend to earth during periods of cultural transition and appear as passerbys, accompanying a human who will have a spiritual task to perform here in the world. They accompany action, transition, movement of the masculine principle (yang). Archetypally, these would be the Three Visitors who appeared to Abraham, the Three Magi, Yeats’ three gnarly Irish with the unicorn in his volume The Gift of the Magi, young Baggins and his three Hobbit travel companions in the Old Forest, the Three Spirits who visit Scrooge in Dickens’ great story of Awakening (the second of whom is certainly the Green Man), the Buddha and the Three Messengers, Johnny Cash and the Tennessee Three and on the pop-culture scale, the three Men in Black of sci-fi folk lore of the 1950s, now a pop movie hit, and the three Lone Gunmen, who advise agent Fox Mulder of The X Files in his quest for the Truth. The Chosen One frequently returns as one of the Three Celestial Ones: Jesus appears with two almost identical white-robed male figures on identical thrones as the Trinity in a 15th-century French Book of Hours, and Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob become the Three Jolly Fishermen. Three Men in a Boat (like the shrewd advisors who fly across the stage in The Magic Flute) shows the Three Celestial Ones in one of their favorite containers. A boat is a gynecological shape, a

There is a Taoist myth of the Three Celestial Ones, the Celestial Worthy of Primordial Being, the Celestial Worthy of Numinous Treasure and the Celestial Worthy of the Way and Its Power, three male deities who are said to live beyond the Big Dipper. They descend to earth during periods of cultural transition and appear as passerbys, accompanying a human who will have a spiritual task to perform here in the world. They accompany action, transition, movement of the masculine principle (yang). Archetypally, these would be the Three Visitors who appeared to Abraham, the Three Magi, Yeats’ three gnarly Irish with the unicorn in his volume The Gift of the Magi, young Baggins and his three Hobbit travel companions in the Old Forest, the Three Spirits who visit Scrooge in Dickens’ great story of Awakening (the second of whom is certainly the Green Man), the Buddha and the Three Messengers, Johnny Cash and the Tennessee Three and on the pop-culture scale, the three Men in Black of sci-fi folk lore of the 1950s, now a pop movie hit, and the three Lone Gunmen, who advise agent Fox Mulder of The X Files in his quest for the Truth. The Chosen One frequently returns as one of the Three Celestial Ones: Jesus appears with two almost identical white-robed male figures on identical thrones as the Trinity in a 15th-century French Book of Hours, and Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob become the Three Jolly Fishermen. Three Men in a Boat (like the shrewd advisors who fly across the stage in The Magic Flute) shows the Three Celestial Ones in one of their favorite containers. A boat is a gynecological shape, a gateway to the sea, the psychic or feminine field, as the Three Celestial Ones rise out of the unconscious. (Boats - Nina, Pinta, Santa Maria - are invariably named after women.)

gateway to the sea, the psychic or feminine field, as the Three Celestial Ones rise out of the unconscious. (Boats - Nina, Pinta, Santa Maria - are invariably named after women.)

Artists, and not only great but also good and competent artists, know instinctively about archetypes and psychic manifestations. A friend of mine, Joe King, who painted portraits of the wealthy and influencial in North Carolina, once did a portrait of a well-known philanthropist from a tobacco family, and in the background he painted a sail boat alone in the distance out at sea with a dark sky, as the gentleman in the portrait enjoyed sailing. The day he finished the painting he discovered, as he prepared to ship it, that the man had just died. A ship or a boat at sea is a folkoric symbol of death as well as birth. It was the only painting King ever did with a boat sailing alone in the distance like that. This is a relationship between parallel events that C.G. Jung called synchronicity, and artists are most conductive to this native intuition.

The Three Celestial Ones precede Lao Tsu and recede into Chinese Taoism up to 5,000 years. Lore has it that like their sisters, the Three Women, each has an second face; a dark nature, which contains the unexpressed characteristics of their life force. And so there are really six. Twelve, counting the Three Celestial Ones and the Three Women together with their Dark Sides, composing the dozen signs of the zodiac, six yin and six yang. The double is usually hard to find and it sometimes takes a Wizard. But in the last five hundred years with the rise of the West, the three agents of the ascending masculine principle (yang - what Vermonter Scott Nearing called the Power Principle),

The Three Celestial Ones precede Lao Tsu and recede into Chinese Taoism up to 5,000 years. Lore has it that like their sisters, the Three Women, each has an second face; a dark nature, which contains the unexpressed characteristics of their life force. And so there are really six. Twelve, counting the Three Celestial Ones and the Three Women together with their Dark Sides, composing the dozen signs of the zodiac, six yin and six yang. The double is usually hard to find and it sometimes takes a Wizard. But in the last five hundred years with the rise of the West, the three agents of the ascending masculine principle (yang - what Vermonter Scott Nearing called the Power Principle),

The West began its outward extension with

The period of the exclusive reign of the Power Principal is entrance and resolve of the High Renaissance, the period described by Jacques Barzun in his book From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life. Three pivotal figures accompany this rise and the ascent of power. They are Isaac Newton (1642-1727), Charles Darwin (1809-1892) and Sigmund Freud (1856-1939).

In the Star Wars series, director George Lucas uses the two faces as a theme throughout. Jedi Master Mace Windu ruminated, after the sith had been dispatched in The Phantom Empire, that they always come in twos. (As does the Princess.) The question was, which was the good guy and which the bad guy? (Likewise, many cartoons since, like Pokemon and Shaman King, and many computer games are influenced by the East and have incorporated Zen themes and psychological patterns. Currently, in Prince of Persia: Warrior Within, for example,

In the Star Wars series, director George Lucas uses the two faces as a theme throughout. Jedi Master Mace Windu ruminated, after the sith had been dispatched in The Phantom Empire, that they always come in twos. (As does the Princess.) The question was, which was the good guy and which the bad guy? (Likewise, many cartoons since, like Pokemon and Shaman King, and many computer games are influenced by the East and have incorporated Zen themes and psychological patterns. Currently, in Prince of Persia: Warrior Within, for example, the Warrior has dual nature, light and dark, as everyone has dual nature.)

the Warrior has dual nature, light and dark, as everyone has dual nature.)

So it is with

The views of

Merchant writes that the world we lost in the rise of the Power Principle was the organic world. From the obscure origins of our species, she said, human beings have lived in daily, immediate, organic relation with the natural order for their sustenance. In 1500, the daily interaction with nature was still structured for most Europeans, as it was for other peoples, by close-knit, cooperative, organic communities. Nature is female, writes Merchant, and as Western culture became increasingly mechanized in the 1600s, the female earth and virgin earth spirit were subdued by the machine.

“The female earth was central to the organic cosmology that was undermined by the Scientific Revolution and the rise of a market-oriented culture in early modern  movement has reawakened interest in the values and concepts associated historically with the premodern organic world. The ecology model and its associated ethics make possible a fresh and critical interpretation of the rise of modern science in the crucial period when our cosmos ceased to be viewed as an organism and became instead a machine,” she writes.

movement has reawakened interest in the values and concepts associated historically with the premodern organic world. The ecology model and its associated ethics make possible a fresh and critical interpretation of the rise of modern science in the crucial period when our cosmos ceased to be viewed as an organism and became instead a machine,” she writes.

The critical turning point, she argues, came with

This contrasted with Leibniz’s view, which saw the world of substance as organic. Every being in the universe, from living animals down to the simple monad, was alive or composed of living parts.

This contrasted with Leibniz’s view, which saw the world of substance as organic. Every being in the universe, from living animals down to the simple monad, was alive or composed of living parts.

Leibniz’s dynamic vitalism was in direct opposition to that of

“Leibniz stressed the idea of a life and perception permeating all things,” she writes. “The main distinction between his philosophy and that of the mechanists lay in the idea that substance was life, not dead matter. He criticized the ‘advocates of the new philosophy’ for ‘maintain[ing] the inertness and deadness of things.’ As he had once written to Jansenist theologian Antoine Arnauld (1612-1694): ‘All matter must be full of animated, or at least living, substances.’”

“During the three centuries in which the mechanical world view became the philosophical ideology of Western culture, industrialization coupled with the exploitation of natural resources began to fundamentally alter the character and quality of human life. Through popular scientific education, through commonsense empirical philosophy and natural religion, and through the spread of scientific, rationalizing tendencies to manufacturing, government bureaucracies, and medical and legal systems, the mechanical science, method, and philosophy created in the seventeenth century have gradually become institutionalized as a form of life in the Western world,” she states.

bureaucracies, and medical and legal systems, the mechanical science, method, and philosophy created in the seventeenth century have gradually become institutionalized as a form of life in the Western world,” she states.

It is interesting and maybe useful to note that the European left his rich inner life, a life, writes Merchant in which, “The earth was alive and considered to be a beneficent, receptive, nurturing female,” with Columbus for the acquisition of the culture of an outer life: goods, action, worlds to conquer and convert, and that Columbus began this adventure on a journey to the East, to the Spice Islands in particular. But this world, recently described by anthropologists and filmmakers Lawrence and Lorne Blair as among the richest places on earth; is not so rich in material goods as it is in spiritual goods.

The Blair brothers describe the Spice Islands and surrounding

The Blair brothers describe the Spice Islands and surrounding

Like

Like the relationships between  theory) without his essential contribution.” The results of this contention, he says, “ … has profoundly affected the subsequent tenor of both science and the humanities.”

theory) without his essential contribution.” The results of this contention, he says, “ … has profoundly affected the subsequent tenor of both science and the humanities.”

It was Wallace’s paper that came first, says Blair, which forced publication of

“’Survival of the strongest,’ for instance, and its tooth-and-claw ethic which became associated with Social Darwinism, is not at all what Wallace had meant by ‘survival of the fittest,’ where fitness was defined by him as a far subtler and more complex weave of forces than mere pugnacious self-interest. A further major difference was in the two men’s attitudes towards tribal peoples – whom Wallace recognized as fascinating equals, rather than as ‘a lower order of the human race’, which was

Wallace believed that natural selection’s checks and balances were not the only forces in evolutionary play but also saw spirit or mind playing through matter. As with

Recently, a new translation of the I Ching, the ancient Chinese book of oracle, was translated by Kerson Huang, a distinguished theoretical physicist at MIT, and his wife Rosemary. It contains an essay in which Huangs point out that Leibnitz did not consider his discovery of calculus to be a new idea, because he had received a copy of the I Ching from a Jesuit friend in

Recently, a new translation of the I Ching, the ancient Chinese book of oracle, was translated by Kerson Huang, a distinguished theoretical physicist at MIT, and his wife Rosemary. It contains an essay in which Huangs point out that Leibnitz did not consider his discovery of calculus to be a new idea, because he had received a copy of the I Ching from a Jesuit friend in

But the world has moved away from the rigidly mechanistic world view of the 19th century, they write, and physics is no longer able to get away with drastic idealizations because it deals with simple measuring instruments, such as scales that read between 1 and 10.

“Everything not in the domain clearly marked out by physics is beyond its grasp, and this is the domain in which the I Ching and other nonscientific endeavors operate. The domain is vast, including such diverse phenomena as the stock market, classical music, and love,” they write. “In fact, it covers all situations and phenomena in which the ‘measuring device’ is a person.”

Not only in calculus and physics have these comparisons been made. In 1974, molecular biologist Harvey Baily observed that the mathematical structure of the DNA molecule is strictly analogous to the structure of the In ching. See John F. Yan's DNA and the I Ching: The Tao of Life.

In each of these three thinkers,  wholeness that pervades Eastern thinking and is pronounced in Tibetan Buddhism. And Wallace's picture of natural evolution, which was imbued by mind and spirit, resembles the Hindu story of evolution.

wholeness that pervades Eastern thinking and is pronounced in Tibetan Buddhism. And Wallace's picture of natural evolution, which was imbued by mind and spirit, resembles the Hindu story of evolution.

At the end of his life

The point has been made by many that the public misunderstanding of scientific principles, particularly those of

But that began to change radically in the academic world in 1962 with the publication of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions by Thomas S. Kuhn. Kuhn shifted the culture at its base. And largely by a popular misunderstanding or no understanding at all of his book. Kuhn gave the academic and professional management world common usage of the word paradigm, and the world was ready for this word and its application – as in, change the paradigm or subvert the dominant paradigm – by the late 1980s and the early 1990s.

But that began to change radically in the academic world in 1962 with the publication of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions by Thomas S. Kuhn. Kuhn shifted the culture at its base. And largely by a popular misunderstanding or no understanding at all of his book. Kuhn gave the academic and professional management world common usage of the word paradigm, and the world was ready for this word and its application – as in, change the paradigm or subvert the dominant paradigm – by the late 1980s and the early 1990s.

In fact, Kuhn changed the dominant paradigm within academic and management culture, but probably more by accident than intention. And if the world was ready for change in the 17th century if not before, it is ready for change again. And, again, it isn’t really important how the scientist or the science historian understands Kuhn’s work. What is important is how the general public misunderstands his work.

And the conventional understanding of Kuhn’s book to those in the professional and academic arenas can fit on a 3 x 5 card: it is that scientific revolutions come and go like religious revivals, build to an arc, then disappear, gone with the wind, like the Anasazi or Tree Druids.

Tree Druids.

Now the paradigm had shifted.

No comments:

Post a Comment