This and the other Appendixes originally were in my notes but didn’t fit in any text, but are interesting and amend what has been said. This part is about Tolstoy. He is most important and has been undervalued primarily because English professors who like his novels don’t like the second part of his life. But this second life has been the foundation of Gandhi’s non-violent movement in

This and the other Appendixes originally were in my notes but didn’t fit in any text, but are interesting and amend what has been said. This part is about Tolstoy. He is most important and has been undervalued primarily because English professors who like his novels don’t like the second part of his life. But this second life has been the foundation of Gandhi’s non-violent movement in What is also important in Tolstoy is how he approached his old age. William James’ great book, The Variety of Religious Experiences should be required reading for those approaching 60 years old and I read in the paper this morning that there are approximately 80 million Americans approaching 60 in the next 20 years or so. Actual war babies, those born in 1946, turn 60 this year. It brings a crisis equivalent to adolescence, and it is a turning everyone must take.

Somebody tell the  madness, to which the once important and famous, from Einstein to

madness, to which the once important and famous, from Einstein to

For men in late 50s and 60s, the body depletes its driving hormones and the Mask of Death appears on the horizon and in your dreams. This, in the quaint phrase of

When I had journeyed half of our life’s way

I found myself within a shadowed forest,

for I had lost the path that does not stray.

In a very different era but at precisely the same mid-life juncture, fictional Mafia boss Tony Soprano suddenly falls into a similar collapse at the sight of a flock of ducks taking flight. Like Dante, Soprano finds his Beatrice; a female psychiatrist who brings him into the world of the Unconscious. This brilliantly written, acted and designed production clearly begins with Dante: “The morning on the day I got sick I’d been thinking,” Tony tells his Beatrice in the first episode, “. . . its good to be in on something from the ground floor, and I came to late for that . . . I know . . . but lately, I’m getting the feeling that I came in at the end . . . the best is over.”

Tony Soprano is the working-class hero trying to find his way between old world and new world without succumbing to narcissism, individualism or the egregious business-class ethos of the “Wonder Bread wops.” Family, honor, duty, dharma, outcasts of the culture of denial, novelty, nihilism and eccentricity, today hide in Gangster Movies. But Tony's essential problem is disenchantment with his mid-life’s work after it has arced.

If you can travel through this chasm it can be your most creative passage – as it was with Dante and ultimately with Tony Soprano. It is like that described by J.R.R. Tolkien as a journey to Middle Earth. “So it went on, until his forties were running out, and his fiftieth birthday was drawing near: fifty was a number that he felt was somehow significant (or ominous); it was at any rate at that age that adventure had suddenly befallen Bilbo.” In fact, Tolkien, born in 1892, was himself just entering his fifties when he began his great work, The Lord of the Rings (composed between 1936 to 1949).

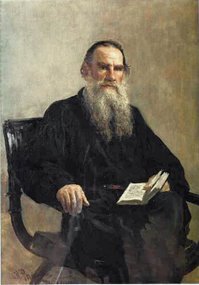

Probably one of the greatest and most creative middle life crises was by that “primitive oak” of a man, as William James called him, Leo Tolstoy, and his tenacious ability to carry through with it could be a lesson for today.

Probably one of the greatest and most creative middle life crises was by that “primitive oak” of a man, as William James called him, Leo Tolstoy, and his tenacious ability to carry through with it could be a lesson for today.

In his biographical book, Confession, written when he was 51, Tolstoy describes his previous life of literary fame lived on instinct, until five years before when something very strange started happening: “At first I began experiencing moments of bewilderment; my life would come to a standstill, as if I did no know how to live or what to do, and I felt lost and fell into despair. But they passed and I continued to live as before. Then these moments of bewilderment started to recur more frequently, always taking the same form. On these occasions, when life came to a standstill, the same questions always arose: ‘Why? What comes next?’”

And then, he continues, what happens to everyone stricken with a fatal inner disease happened to him: “At first minor signs of indisposition appear, which the sick person ignores; then these symptoms appear more and more frequently, merging into one interrupted period of suffering. The suffering increases and before the sick man realized what is happening he discovers that the thing he had taken for an indisposition is in fact the thing that is more important to him than anything in the world: it is death.”

At this turning point Tolstoy gave up entirely any interest in his literary work and took himself completely out of that period of this life to the work he would address in the next. Like many do at this transition, he turned to the church to which he was born, the Russian Orthodox Church. But here he faced the dilemma many of us face today.

When he returned to the Orthodox Church, he would not simply bow to the authoritarianism of the priests, but consider his own condition, and there he found a conflict.

Tolstoy grew up in the Age of Reason with a church from a previous age, and he was unable to reconcile the two. Rather than accept the authority of the church and believing on blind faith, which denied the integrity of the human being, he began to study other religions including Taoism, Buddhism, Islam and the Ba’hai religion, which was just taking shape in

When he embarked on his study of Christianity he felt himself, “. . . in the position of a man to whom is given a sack of refuse, who, after long struggle and wearisome labor, discovers among the refuse a number of infinitely precious pearls.” He decided to start from scratch, learned Greek and Aramaic, and translated the Gospel by himself, calling it The Gospel in Brief, because it left out what he considered to be side-show trickery, such as “the walking on the sea, and the raising of the dead.” These he omitted, he said, “… because contains nothing of the teaching and describing only events which passed before, during, or after the period in which Jesus taught, they complicate the exposition.” Their sole significance for Christianity, he wrote, was that they proved the divinity of Jesus Christ for him who was not persuaded of his divinity beforehand.

Tolstoy’s dilemma is our own dilemma. He grew up in a religion built with dogma and authoritarianism. Then he took off that coat and put it aside to enter his adult life. As he passed into old age he went back to his original church. This is the way it was done effectively for all time and at all places, as the going back takes place through the same gate through which one enters. But here he found that the coat he put aside in his youth did not fit and that there was no portal for him to enter into death.

Nor does it fit today. This is the Aquarian dilemma for the first few generations growing up in a new century. The old coat belongs to an age that is past and it no longer fits. It is a particularly American dilemma. Tolstoy’s solution was to build an entire religion firsthand, one with features of Taoism and Buddhism, but one he found within himself, echoing the ancient strains of the early Russian Orthodox and the Muslim of the

As one of his biographers said, Tolstoy was, in this period, a “being of evolution.”

We will begin to find our way forward in this new century and in the first centuries after this. Tolstoy may serve as a guide, as he did to the non-violent leaders of the Civil Rights Movement and the anti-war movement in the 1960s. In his rigorous analysis and lucid proscription for action without violence, Tolstoy Awakened a new world. And those who grew up in an Englightenment tradition and still were instructed in the New Testament in youth will find his translation, The Gospel in Brief, instructive. When I read it I asked a dozen people raised Christian what the "moneylenders" at the temple were selling. No one knew the answer. They were selling animals for the purpose of blood sacrifice in the Temple. It is this which Jesus raged against. The conventional view based on the King James translation is that Jesus was angered at the Jews for sellling things on the Sabbath. This makes no sense. There is nothing in Christ's life which makes him a fetish for Blue Laws. John 2:13-16, which relates the passage, makes no mention of blood sacrifice. The conventional translations change the story of Christ's life to fit the social scene of the early 1600s. As the English commerce class was rising, anti-Semetic pressures were growing and this passage as told created a mainstain charicature of Jews as petty and unethical financial dealers. If you Google the phrase "moneylenders in the Temple" today you find anti-Islamic entries - a new twist on a traditional Jew-as-Moneylender refrain. This passage as Tolstoy translates it makes an important point which has been twisted by Christian historians who have customized a Designer Christ to amend their own historiocal epochs. Tolstoy shows that as a Jewish reformer, one of the reforms Christ desired was the abandonment of blood sacrifice as barbaric and tribal. The Hebrews in fact abandoned this practise, but the Roman Church fathers, in conquering the northern lands, sublimated the Pagan practise of animal and human sacrifice as the primary ritual of the church, The Sacrifice of the Mass.

No comments:

Post a Comment